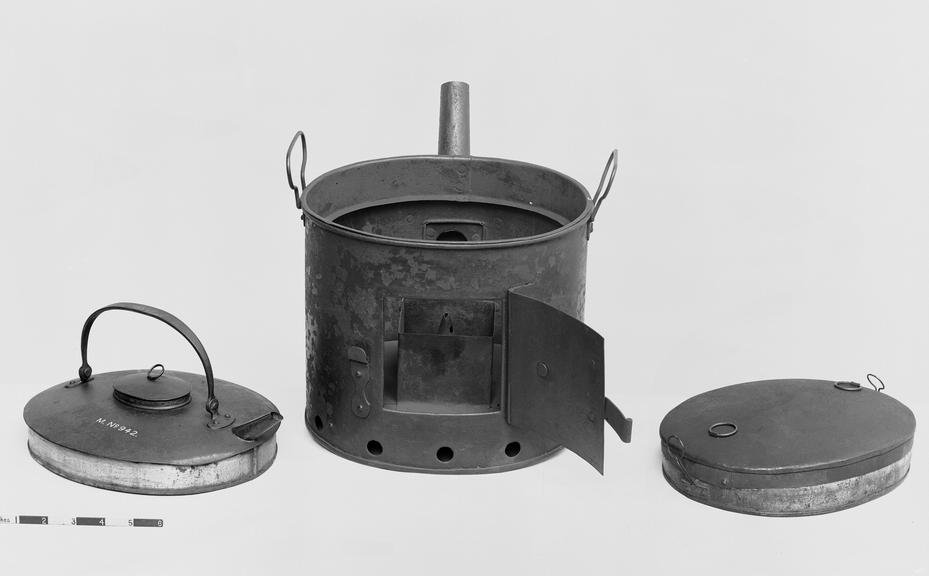

Water kettle from a Bachelor's Stove by James Watt

Water kettle part of a Bachelor's Stove, reputedly designed and used by James Watt, English, 1760

More

By designing steam engines, James Watt became one of the most influential engineers ever. His work helped define what an engineer is. By longstanding repute, his career began with childhood experiments – watching steam lifting a kettle’s lid as it boiled. This moment became a parable for successive generations, recreated in many graphical forms.

The nineteenth century fascination with the kettle story is neatly encapsulated in the acquisition of this item by the Patent Office Museum, predecessor of the Science Museum, in 1863. Francis Pettit-Smith, the museum’s curator, was in touch with JW Gibson-Watt, then head of the Watt family, concerning a ‘kettle’ said to be in his possession which had belonged to James Watt himself. After some consideration, Gibson-Watt wrote that although the kettle had been removed by James Watt Junior from his father’s home following his death in 1819, it was ‘not a “tea kettle” at all, and I am satisfied it is not… the one which he originally observed the steam lifting the lid when boiling on the fire’. However, it was ‘evidently made by his orders and used as an experimentalising steam kettle, it has a moveable funnel and two parts that lift out’. Francis Pettit Smith remained intrigued, replying that ‘of course the identical kettle referred to in the paper article would have been if possible more interesting than the one which you have in your possession. Still as this one was actually constructed for and used by James Watt in his early investigations of the properties of steam it cannot fail to attract great notice and prove to be a very interesting + valuable acquisition’. The kettle was subsequently delivered to the Patent Office Museum by Richard Banks, Gibson-Watt’s solicitor.

The mythology surrounding James Watt makes this one of the most intriguing objects in the Science Museum's steam-related collections. JW Gibson-Watt's assertion that it is not a tea kettle is questionable: research suggests that the complete set of charcoal-fired heater, kettle and warming pan was most likely made for travelling purposes, and could well have been used for tea-making. It is made of tin-plate, and seems in keeping with the tradition of useful metalwares coming from Birmingham and other metalworking centres during the period in question. There is maybe some wishful thinking in FP Smith's insistence that 'this one was actually constructed for and used by James Watt in his early investigations of the properties of steam'. That aligns with the phenomenon identified by historian David Miller in his research around Watt of artefacts claimed to be associated with him on somewhat dubious foundations being created 'from the materials of company folklore' in the engineering company founded by Watt with Matthew Boulton, which maintained a museum of artefacts associated with the early history of the steam engine. But, on the other hand, the provenance of the object and its associations directly to Watt do seem to be in place.

Maybe given the mythic status of Watt, what matters with this object is not so much what it actually is, but what successive generations of people have thought it to be.