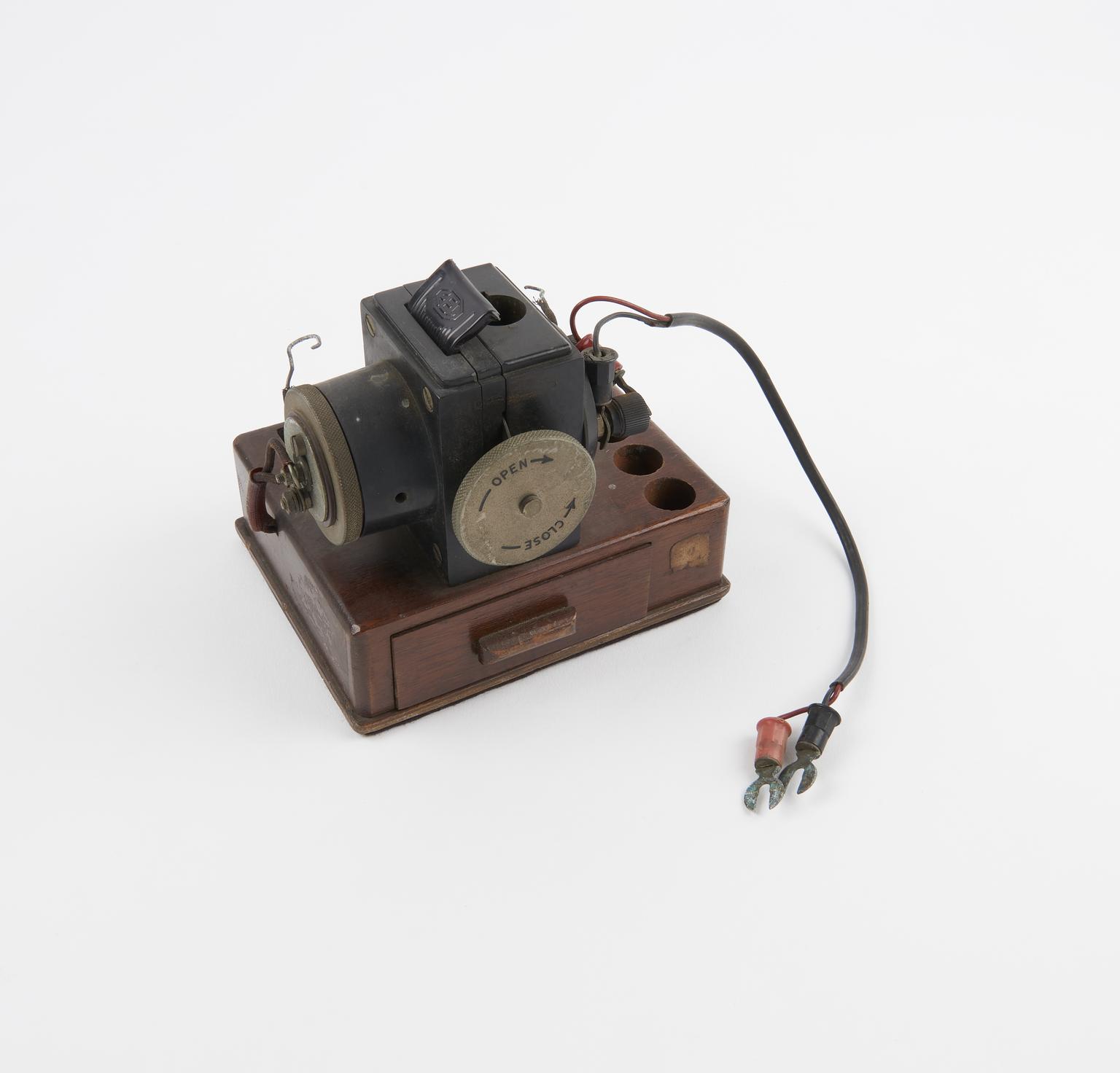

Haemoglobinometer used on 1953 Mount Everest Expedition

King photo-electric haemoglobinometer, used with a galvanometer by Dr Griffith Pugh during the 1952 Mount Cho Oyu expediation to provide physiological data for the Mount Everest expedition of 1953, and used on that Everest expedition also, United Kingdom, 1952-3.

More

What does it take to climb Everest, the world’s tallest mountain? Preparations for the 1953 Everest attempt began in 1952 with a reconnaissance and research trip to Mount Cho Oyu, about 20km west of Everest and the world’s sixth highest mountain. During this trip, one of the areas researched by physiologist Dr Griffith Pugh was the affects of altitude on the body. This King photo-electric haemoglobinometer with galvanometer was used to measure changes to haemoglobin levels in the blood as the body adapts to changes in altitude. As early as 1871, it had been found that in response to high altitude the body produces more haemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in the blood. However, Pugh’s research in the Himalayas found that levels of haemoglobin in the blood were not a reliable indicator of how well people would perform at high altitudes. Pugh placed much more emphasis and importance on a slow and steady climbing programme, with climbers resting at lower altitudes to allow them to acclimatise to high altitudes.

By the 1950s, there had been several attempts to summit Everest and some climbers had got very close, but none had made it. The pioneering research of Dr Griffith Pugh was a key factor in the success of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s climb in 1953. Pugh’s background made him uniquely suited to this work. He was a practising doctor, but also a world class skier. He was selected to represent Great Britain in skiing at the 1936 Winter Olympics, but he was unable to attend due to injury. He also trained soldiers at the School of Mountain Warfare in Lebanon during the Second World War. It was here that Pugh began to research the impact of high altitude and extreme conditions on the body, leading to his work on Everest. Pugh took part in the expedition to Everest in 1953 and the preparatory expedition in the Himalayas in 1952, believing that laboratory research could not accurately recreate the experience of being in these extreme environments. His work established principles about acclimatising to altitude, food and water consumption during climbs, and oxygen usage that continued to be used by climbers for decades.

- Measurements:

-

overall: 132 mm x 143 mm x 115 mm,

- Materials:

- wood (unidentified) , metal (unknown) and textile

- Object Number:

- 2017-46/1

- type:

- haemoglobinometer

- Image ©

- The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum