Wheatstone, Charles 1802 - 1875

- Nationality:

- English; British

(1802-1875) Knight Physicist

Sir Charles Wheatstone, developer of telegraphy, was born on the 6th February 1802 at the Manor House, Barnwood, Gloucester. In 1806 the family moved to London, where Wheatstone went to school. At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to an uncle, who had a musical instrument manufacturing business in the Strand. Charles was fascinated by the physics of sound and in 1823 -the same year he took over his Uncle's business with his younger brother William -he contributed to a paper 'Thomson's Annals of Philosophy', describing his early experiments with sound. In 1825 he constructed a mouth organ with free reeds governed by a small button keyboard; further experiments led to the bellows-blown concertina (patent 10,041 of 1844). One of the few original British musical instrument designs, it is still being played at the present time.

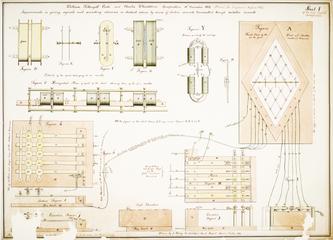

Wheatstone made several important contributions to optics, the stereoscope, was entirely due to Wheatstone. When David Brewster discovered that light from the sky is always polarized in a plane 90° from the sun, Wheatstone devised a clock by which it was possible to tell the hour of the day by the light from the sky even though the sun might be invisible. Although his inventions in other branches of science are numerous, Wheatstone has been most closely connected with the electric telegraph. He was not the ‘inventor’, but Wheatstone, with his collaborator William Fothergill Cooke, is due the credit for having been the first to render it available for the public transmission of messages. In 1834, at about the time he was appointed professor of experimental philosophy at King's College, London, Wheatstone began experimenting on the rate of transmission of electricity along wires. From this research Wheatstone passed on to the transmission of messages by electricity, and, in conjunction with Cooke, he devised the five-needle telegraph, and then the two-needle telegraph, the first that came into general use. This led to many new developments, including the letter-showing dial telegraph in 1840, and the type-printing telegraph in 1841. The automatic transmitting and receiving instruments, by which messages were sent with great rapidity over the telegraph system, were designed by Wheatstone alone, after the partnership with Cooke had been dissolved.

From 1837 Wheatstone devoted a good deal of time to submarine telegraphy, and in 1844 experiments were made in Swansea Bay, with the assistance of J. D. Llewellyn. In 1837 he devised a method of combining several armatures on one shaft so as to generate a continuous current. Wheatstone had many miscellaneous inventions including a share in the development of the electric generator, electro-magnetic clocks for indicating time at any number of different places united on a circuit, a cryptograph, or secret dispatch writer, which was used by the British army, electric chronographs, apparatus for making instruments record automatically, and instruments for measuring electricity and electrical resistance, including the rheostat. It was he who called attention to Christy's combination of wires, commonly known as ‘Wheatstone's bridge’, in which an electric balancing of the currents is obtained, and he worked out its application to electrical measurement. He was one of the first in Britain to appreciate the importance of Ohm's simple law of the relation between electromotive force, resistance of conductors, and resulting current—the law which is the foundation of all electrical engineering. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1836.

Wheatstone married, on 12 February 1847, they had a family of two sons and three daughters. He was made a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur in 1855, and a foreign associate of the Académie des Sciences in 1873. On 2 July 1862 he was created DCL by the University of Oxford, and in 1864 LLD by the University of Cambridge. Moreover he possessed some thirty-four distinctions or diplomas conferred upon him by various governments, universities, and learned societies. On 30 January 1868 he was knighted. He died of bronchitis in the Hôtel du Louvre, Paris, on 19 October 1875.