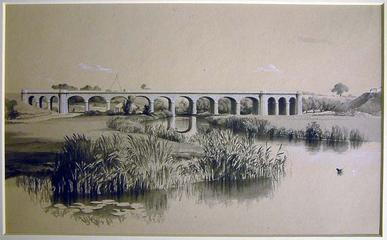

Watercolour of Connagore bungalow and East Indian Railway works in Konnagar, India

- Made:

- 1853-11-03

- maker:

- G W Archer

Painting, watercolour, Connagore bungalow, 2 miles south of Serampore, showing also the railway embankment, 3rd November 1853, by G W Archer. Depicts the construction of a railway embankment by Indian labourers, who are carrying earth in baskets on their heads, and tipping it on the mound. In the foreground a labourer bows low before a British official, who is sheltered beneath a parasol held by another labourer. At right a man in Indian dress holds a white horse, amidst the stumps of cut down trees. Beyond is a two-storey bungalow, set amidst trees, with a veranda on the second floor and a thatched roof. There are two smaller thatched buildings nearby. The title is inscribed in ink on the reverse together with the words "Geo. Turnbull 3 Nov 1853" and in pencil "Drawn by Mr Archer". From the collection of George Turnbull, Chief Engineer of the East Indian Railway. The inscriptions are in Turnbull’s hand.

Connagore (now Konnagar) is a town on the west bank of the Hooghly River. It has a station on the East Indian Railway 15km to the north of the terminus at Howrah/Kolkata. This watercolour shows the construction of the line.

Halfway up the painting, water is visible. Konnagar is a wetland, with many flooded areas. People sometimes used flooded areas as paddy fields to grow rice. The water drained at Bally Khal, a canal off the Hooghly to the south. As more roads and fisheries were built in the area, the drainage system became increasingly blocked. Water stopped flowing to Bally Khal.

In the mid-1870s, the British Raj government sold off surplus railway land to private owners. Many of these owners converted the land into gardens or tanks (artificial reservoirs), further cutting off the drainage system. The increased blockages made annual epidemics in the area worse and more frequent. Digambar Mitra, the first Bengali Sheriff of Kolkata, predicted that with the blockage of the former railway lands, ‘the epidemic will break out with greater virulence after the next rainy season than it has done before’. Sadly he was proved correct, and people who could afford to move away began to do so.

Things eventually improved, and in 1931 Konnagar became home to the first Indian workshop of the Czech shoe brand Bata. The brand remains very popular in modern-day India.

Scottish engineer George Turnbull (1809-1889) oversaw the creation of one of the first railways in India, the East Indian Railway (EIR). The EIR ran from near Calcutta (now Kolkata), an East India Company trading post in the north-east that the Company established as the capital from 1773. The terminus was originally Benares (now Varanasi), but the line quickly extended to New Delhi in the north, which became the capital of India in 1911. Calcutta and New Delhi are over 1,300km miles from each other – further than the distance between Paris, France and Budapest, Hungary.

Turnbull collected artworks during his time in India, many of which were produced by EIR engineers. These watercolours and drawings provide a rare view of nineteenth-century India from the perspective of the British engineers designing and building the country’s first railways. The collection includes landscape scenes and portraits. While many of the landscapes show the construction of the railway, others focus entirely on India’s local architecture or its rural spaces. The portraits are of people Turnbull encountered while in India. While the portraits of British people are inscribed with their names, most of the Indian people depicted remain anonymous or identified only by their job.

The British introduced railways in India to satisfy the mounting economic and military needs of their colonial administration. They hoped that the new technology would foster an increased sense of collective identity by making it easier to travel quickly between distant regions. They also hoped the railways would socially ‘improve India’ by instilling a sense of punctuality among Indians, a quality British colonialists believed Indians lacked. The racist stereotypes underpinning these intentions, and the interconnected idea that technology could trigger social change, were common beliefs in nineteenth-century British society.

Details

- Category:

- Pictorial Collection (Railway)

- Object Number:

- 2017-7094

- Materials:

- Paper, watercolour and ink

- type:

- painting, watercolour