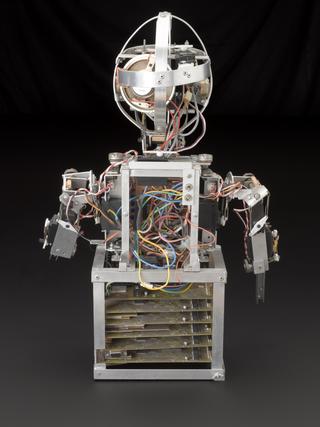

‘Autoperipatetikos’ Walking Doll

Doll section of ‘Autoperipatetikos’ walking doll, by Martin & Runyon, USA, c1862

More

‘Autoperipatetikos’ means ‘the automatic walking one’. The doll has a well-designed spring-driven mechanism concealed beneath her skirts, allowing her to walk forward. The figure was a huge novelty when it was launched , and was the subject of a patent in the USA (Enoch Rice Morrison, 1862). Martin & Runyon also had offices in London from 1862 to 1867, reflecting efforts to market this product internationally.

This object reflects the wide nineteenth century fascination with mechanical figures and other automata – what became known as ‘Steam Men’. A handful of these were human-sized figures, but the very vast majority comprised smaller doll-like figures like this. Production was centred in France, but such was the demand that a substitution effect kicked in, and companies existed in some numbers on the Continent, in the UK and USA too.

The mechanism is an interesting and early example of a figure which could take steps forward, rather than rolling or sitting static with movement concentrated in the upper torso. It is also a piece of technology which would have been used in play and leisure, within a family setting.

The numbers built of such figures – hundreds of thousands in total – mean that, by 1900, the idea of mechanical people was well embedded in popular culture. When Rossum’s Universal Robots was published in 1920, followed by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1928, they were entering a market well-prepared in advance. So, although object like this might seem rather like curios, the cumulative effect was such as to engender a broader interest in, and debate around, what were to become known as ‘robots’.